So far the oldest game to deserve a post on this blog, The Quest for the Rings is my favorite Videopac / Odyssey2 game, and arguably the best. Had it been released in 1985, its computer part (more on this in a minute) would have been described as “a Gauntlet clone”… only it preceded Gauntlet by a full 4 years (and Dandy, the game that inspired Gauntlet, by 2 years).

That, however, wasn’t the extent of QftR’s innovation. It was also, as far as I know (please correct me if I’m wrong, and I’ll edit this post) the first successful combination of a video game and a board game; the game came in an unusually large (and lavish) box, which included not only the game cartridge and (beautifully illustrated) manual, but also a game board and an assortment of game pieces, plus a keyboard overlay for selecting game options. Also, it was a cooperative game at a time where that was truly rare (I don’t know of a co-op game before this one, but it’s likely that one exists). Oh, and it had four character classes for the players to choose from. Remember that all of this was at a time of games such as Pac-Man and Frogger.

As you can imagine, the full game was relatively complex, especially when compared to most videogames at the time, and also took a long time to play. It was supposed to be played by at least three inviduals: two of them playing the heroes, and the other playing the Ringmaster. No, not the kind from a circus; think of a D&D Dungeon Master, but openly working against the players (though limited by the game’s rules). The heroes had a time limit of a certain number of turns to find and collect ten rings, hidden among a larger number of castles, while the Ringmaster did everything in his power to prevent them from doing so; if the time limit expired, the RM won the game.

The castles were designed so that they could cover other pieces (rings and/or monsters); the castle pieces also had, on the inside, a design of a dungeon type. In other words, both the contents of a castle and the type of castle itself were hidden from players… until they attempted to enter it.

Besides setting up the game board (with the location of the rings and special monsters hidden from the heroes), the RM could sometimes move some of the monsters around, and also occasionally “possess” one of the players, which, imaginatively, meant that the joypad during the next castle’s action sequence was actually handed to him — and, naturally, he would do his best to make the other player fail that sequence (and they are usually hard enough with both players cooperating), therefore making the heroes lose time.

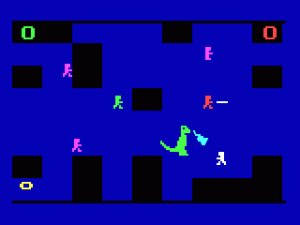

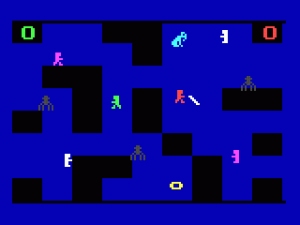

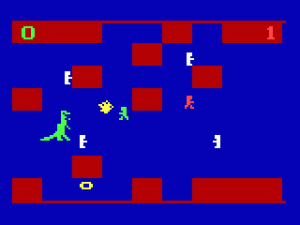

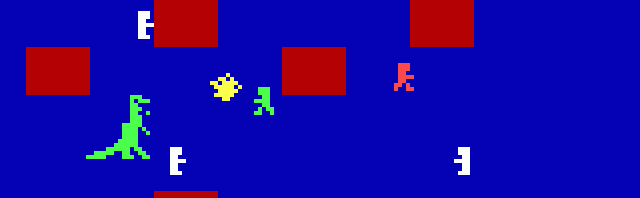

All this and I haven’t even mentioned the actual “video” part of the game, right? As the screens (may) suggest, each castle was a single screen, with some walls, monsters, and either a ring or an exit. If the players died without reaching either, they would lose time, and could try again ((if there was no ring, the players couldn’t move on to another place on the board map until they succeeded in reaching the exit — losing time each time they failed. Just in case you were wondered why players didn’t just kill themselves and move on if they entered a castle and found there was no ring in it…)).

As mentioned before, there were four character classes to choose from: the Warrior, who had a sword that killed humanoid monsters (though new ones appeared at the edge of the dungeon whenever he did that), repelled the more powerful monsters, and could even stop the dragons’ fire, as long as the player’s timing was good. He could only attack horizontally, though, and the sword had a very short range. The Wizard had a ranged attack (again, fired horizontally only), but it only stunned monsters for a while, instead of killing or repelling them. The Phantom could travel through walls (except one kind), though he did so at half speed; he could either use that power to get to the ring without having to go around walls (which the monsters had to do), or simply enter a wall and attract monsters from a position of safety, while the other player went for the ring. Finally, the Changeling could turn invisible, by holding the fire button; when doing so he didn’t attract monsters (though he could still be killed if he touched one), but on the other hand he was invisible even to the player, requiring either memory and planning, or brief (and dangerous, since he had no way to defend himself) moments of visibility for the player to check his position.

Some of the classes were obviously easier to play than others, and there were some combinations that worked especially well — such as a Warrior and a Wizard (both ranged power and killing power), or a Phantom and a Changeling (one would enter a wall, the other would stay invisible for a while, and since the monsters could only see the Phantom, they would all go to him, and the Changeling could then grab the ring unimpeded). The players succeeded as long as one of them reached the ring or the exit, so distraction tactics such as the above, and even sacrifices, were common — and effective.

As there were four character classes, so were there four castle types: Dungeons (simple walls), Crystal Caverns (invisible walls, except when a player was touching them — but they were visible to the monsters, naturally), Infernal Infernoes (great name 🙂 ; they killed any player who touched them, even a Phantom — thus making that class useless on those levels, except as mere monster bait (which should not be discounted), and Shifting Halls (every few seconds, all walls moved one space from left to right, possibly trapping players and monsters inside them — except for the Phantom, of course, who finally came into his own, being unaffected while the other player classes and monsters would be trapped again and again).

And, finally, the monsters. Can you guess how many types there were? 🙂 Nope, technically you’re wrong: there were five kinds — though two of them are so similar that they could be considered just one monster type. These two are the Orcs and Firewraiths, who look like each other except for the color (the latter are pink instead of white), and the fact that the Firewraiths are a bit faster. These two monster types exist in all dungeons, independently of the presence or absense of other monsters. Then there are the unkillable Dragons, which move left and right in the vertical middle of the screen, but when they spot a hero they both charge him at a much greater speed… and breathe fire at him (which can be stopped by the Warrior’s sword or the Wizard’s spell, but it requires very precise timing, since the fire is so fast; more often than not the player is simply burned to a crisp. The best way to pass through a dragon is… to do so quickly, when he is either roasting or devouring the other player. 🙂

The final two monsters are collectively called The Nightmares, and they always appear together (indeed, in the board game they’re a single token). They also have some of the most awesome names ever 🙂 : the Spydroth Tyrantulus ((note that some sites about the game misspell it as “Tarantulus”)), basically a giant spider which, the manual tells us, “delights in the devouring of living flesh which it believes will enhance its life span”, and which, when above the player, can descend to him at twice its normal speed, and, wait for it, the Doomwinged Bloodthirsts, a name that any goth readers are currently kicking themselves for not having come up with. (Sorry, guys, you’re 30 years too late.) They’re big vampire bats, who also move in a strange way — moving and pausing, moving and pausing — and, when still, can’t be repelled by the Warrior’s sword. Oh, and did I mention that both Nightmares, much like the Dragons, cannot be killed?

So, that’s the “video” part of QftR. Now, I have to admit: I and my brother and friends, at the time, only played the full game (with the board, tokens and so on) a couple of times, since we didn’t find it very enjoyable; games were too long, and it was basically a player trying to screw things up for the others, to delay them. In other ways, either the Ringmaster “rolled over” for the players, or, if he was good, he would only be frustrating them.

Fortunately, the game had another option, which was how we played it almost all the time: what could be called an “action quest”. This time, there was no Ringmaster, and no board: all the action was on the console. After the two players chose their classes, the computer would circle them through the various combinations of castle types and monsters (i.e. Dungeons & Dragon (!), Dungeons & Nightmares, Crystal Caverns & Dragon, and so on, starting over after the last combination). All castles had rings, and the game ended when both players together had collected 10 rings — though the game still kept separate scores, to provide for a little competition. But it was, at heart, a cooperative game, and many effective tactics required both players working in tandem.

So, if you’ve read thus far… don’t you agree that this game is begging for some kind of remake? 🙂

Ah, good old #42… I guess a remake would be pretty sweet, they can update the graphics a bit and sell it for €70. 🙂

Actually, I think I have a few good ideas for a remake, which will be the subject of a future post, and perhaps even a new series: “How would I remake game X”?